You know that moment? The one where you walk into a bakery, and the warm, buttery aroma hits you like a hug from your favorite person. You grab a croissant—golden, flaky, just slightly crisp on the outside—and take that first bite. Crumble. Soft. Rich. Heavenly.

But have you ever stopped to wonder why it tastes like magic?

Is it just the butter? The skill of the baker? Or is there something deeper—a science, an art, a centuries-old technique hidden in those delicate layers?

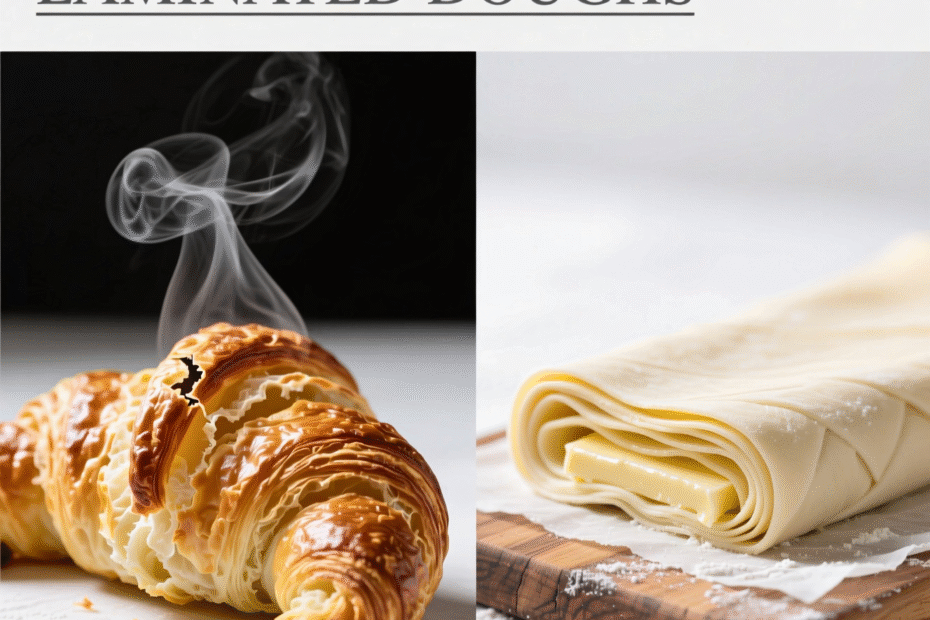

Welcome to the deliciously layered world of butter croissants vs. laminated doughs.

This isn’t just about breakfast pastries. It’s about understanding how simple ingredients—flour, water, salt, yeast, and butter—can transform into something extraordinary through patience, precision, and a little bit of love.

Whether you’re a home baker dreaming of perfect flakiness, a food lover curious about what makes your morning treat so irresistible, or someone who just wants to know why their homemade croissants turn out dense instead of dreamy—this article is for you.

We’ll unpack the real difference between butter croissants and other laminated doughs, explore the science behind layering, debunk common myths, share practical tips you can use today, and even reveal why some “croissants” sold in supermarkets aren’t really croissants at all.

By the end, you won’t just know the difference—you’ll be able to spot it, taste it, and maybe even make it yourself.

Let’s dive in.

What Exactly Is Laminated Dough?

Laminated dough might sound like a fancy term from a baking textbook, but here’s the truth: it’s just dough with butter folded inside—over and over again.

Think of it like making a puff pastry sandwich: you roll out dough, lay a block of cold butter on top, fold it up, roll it again, fold it again… repeat this process several times. Each fold creates a new layer of dough and a new layer of butter. When baked, the water in the butter turns to steam, pushing those layers apart—and boom! You get flakiness. Pure, buttery, airy flakiness.

This technique dates back to 17th-century Austria, where bakers started experimenting with folding butter into yeast doughs. Eventually, it evolved into what we now call pâte feuilletée (French for “leaf dough”)—the foundation of everything from croissants to pain au chocolat, danishes, and even savory turnovers.

So here’s the key point: All butter croissants are laminated doughs—but not all laminated doughs are croissants.

That’s the first big takeaway.

Croissants are a type of laminated dough—they’re enriched with milk, sugar, and yeast, giving them a softer, slightly sweet, bread-like texture. Other laminated doughs, like puff pastry, contain no yeast at all. They rely purely on steam for lift. Danishes? They’re also laminated—but often sweeter, sometimes filled, and usually shaped differently.

Why does this matter? Because if you think “laminated dough = croissant,” you’re missing out on the full spectrum of possibilities. And worse—you might be confusing a mass-produced, shortening-based “croissant” (yes, they exist) with the real deal.

In fact, the European Union legally defines a true croissant as one made with at least 20% butter and laminated using traditional methods. Many store-bought versions use margarine or vegetable oils—cheaper, longer shelf life, but zero soul.

So next time you buy a “croissant,” ask yourself: Does it melt in your mouth? Does it smell like real butter? Or does it just look like one?

Understanding lamination gives you the power to tell the difference.

Why Butter Makes All the Difference

Let’s talk about butter. Not the kind you spread on toast. We mean high-fat, low-water, cultured European-style butter—the kind professional bakers swear by.

Here’s the secret: It’s not just flavor. It’s physics.

When butter melts during baking, it releases steam. That steam is what pushes the layers apart, creating air pockets—the very essence of flakiness. But not all butter behaves the same way.

Regular supermarket butter (about 80% fat) contains more water and less fat. That means more steam… but also more risk of the dough becoming soggy or greasy.

European-style butter (82–86% fat) has less water, which means cleaner separation between layers. Less mess. More lift.

Cultured butter, made from fermented cream, adds a subtle tangy depth that elevates the entire experience.

I once tried making croissants with two different butters side by side. One was a name-brand American butter. The other was a French cultured butter from a local cheesemonger.

The result?

The American version puffed up nicely—but tasted flat. Like a good performance without emotion.

The French one? Golden, fragrant, with a caramelized edge and a lingering richness that made me close my eyes mid-bite.

That’s the difference butter makes.

And here’s the kicker: The quality of your butter directly impacts how many layers you can successfully achieve.

If your butter is too soft when you’re folding, it oozes out and merges with the dough—no layers. Too hard? It cracks, tears the dough, ruins the structure.

The ideal butter temperature? Around 60–65°F (15–18°C). Cold enough to hold its shape, soft enough to roll smoothly with the dough.

Pro tip: If you’re unsure, press your finger into the butter block. It should leave a slight indentation—not sink in, not feel like ice.

So yes, butter matters. A lot.

Don’t be fooled by recipes that say “use any butter.” Real bakers don’t cut corners here. And neither should you.

The Art of Folding: How Layers Are Born

Now let’s get hands-on.

How do you go from a flat slab of dough to hundreds of paper-thin layers?

It’s called folding, and it’s where the magic happens.

Most traditional croissant dough goes through three to four “turns.” Each turn doubles—or sometimes triples—the number of layers.

Start with one layer of dough and one layer of butter. After the first fold, you’ve got three layers. After the second, nine. After the third? Twenty-seven. After the fourth? Eighty-one.

That’s right—one single croissant can contain over 80 distinct layers of dough and butter.

Imagine rolling out a ball of clay, wrapping it around a stick of butter, then rolling it thin, folding it like a letter, chilling it, rolling it again… and repeating. It’s meditative. It’s exhausting. It’s beautiful.

But here’s where most home bakers fail: patience.

Each fold requires chilling the dough for at least 30–60 minutes. Why? Because butter must stay firm while the gluten relaxes. Skip the chill, and your dough shrinks, the butter melts, and your layers vanish.

I remember my first attempt. I rushed. Didn’t chill long enough. The butter leaked out like melted cheese on a pizza. My croissants looked like sad, greasy biscuits.

Lesson learned.

The best advice I got? “Treat the dough like a nervous cat. Be gentle. Give it space. Don’t force it.”

And here’s a pro trick: Use a ruler. Measure your dough before each fold. Consistent thickness = even layers = consistent rise.

Also, keep your kitchen cool. If it’s hot outside, work early in the morning. Use a chilled marble countertop. Place your dough in the fridge between folds—even if the recipe doesn’t say to.

It’s not just tradition. It’s science.

And the payoff? A croissant that shatters beautifully at the touch, with airy holes inside, and a scent that fills your whole house like a memory of Parisian mornings.

Croissants vs. Other Laminated Doughs: What Sets Them Apart?

Let’s clear up a common confusion:

Not every flaky pastry is a croissant.

Take puff pastry. No yeast. No sugar. Just flour, water, salt, and butter. It puffs dramatically because of steam alone. Think vol-au-vent, palmiers, or beef wellington casing. Light? Yes. Bready? No.

Then there’s danish dough. Similar to croissant dough, but often sweeter, richer (sometimes with egg), and usually shaped into spirals, knots, or half-moons. Fillings? Cream cheese, fruit, nuts. Danish is dessert. Croissant? Breakfast.

Pain au chocolat? Technically a croissant—but with chocolate bars embedded inside before baking. Same dough. Different soul.

And then… there’s the imposters.

Many grocery stores sell “croissants” made with hydrogenated oils, pre-made frozen dough, and artificial flavors. They’re fluffy. They’re cheap. But they lack depth. They don’t breathe. They don’t sing.

Here’s how to tell them apart:

Try this experiment: Buy one authentic croissant from a real bakery and one from a supermarket. Eat them back-to-back. Close your eyes.

You’ll know instantly.

And if you want to elevate your own baking? Start by matching the dough type to the goal.

Want light, airy, savory pastries? Go with croissant dough.

Want crispy, delicate pastries with no yeast? Choose puff pastry.

Want something sweet and indulgent? Try Danish.

Knowing the difference lets you choose the right tool for the job—and avoid disappointment.

Bakiking at Home: Simple Tips for Your First Successful Croissant

Feeling inspired? Good.

Here’s the truth: You don’t need a professional oven or a pastry degree to make amazing croissants at home.

You just need:

✅ Patience

✅ Cold butter

✅ A little time

Let me walk you through the essentials—no jargon, no overwhelm.

Step 1: Use the right flour.

All-purpose works fine, but bread flour (higher protein) gives better structure. Don’t overmix.

Step 2: Keep everything cold.

Chill your dough after every fold. Use ice water. Chill your bowl. Even pop your butter block in the freezer for 10 minutes before using if it’s too soft.

Step 3: Roll gently.

Don’t press down hard. Let the roller do the work. If the dough resists, stop. Rest it.

Step 4: Proof properly.

Croissants need to rise slowly—at room temperature, covered, for 2–3 hours. They should double in size and jiggle slightly when nudged. Rushing this step = dense croissants.

Step 5: Bake hot and fast.

Preheat your oven to 400°F (200°C). Bake for 15–20 minutes until deeply golden. A spray of water in the oven at the start helps create a crisp crust.

Bonus hack: Brush with egg wash (1 egg + 1 tbsp water) before baking for that glossy, professional finish.

And here’s the biggest secret of all: Your first batch won’t be perfect. And that’s okay.

Even Jacques Torres, the legendary pastry chef, says his first croissants were “a disaster.”

What separates great bakers from amateurs isn’t talent—it’s persistence.

So bake again tomorrow. And the day after.

Because the reward? A warm croissant fresh from your oven, still steaming, butter glistening at the edges…

That’s worth every sticky counter and tired arm.

The Soul of the Craft: Why This Matters Beyond the Kitchen

Baking laminated doughs isn’t just about food.

It’s about presence.

In a world of instant meals, microwave lunches, and 10-minute recipes, making croissants demands slowness. It asks you to wait. To listen. To feel the dough. To notice when it’s ready—not by a timer, but by sight, by touch, by intuition.

There’s poetry in folding dough. In watching layers form. In smelling the butter bloom as it bakes.

This isn’t just baking. It’s mindfulness with flour.

Think about it: How often do we rush through our days? How many moments do we miss because we’re scrolling, multitasking, rushing?

Making croissants forces you to slow down. To be in the moment.

Every fold is a breath.

Every chill is a pause.

Every rise is a promise.

And when you finally pull those golden crescents from the oven?

You didn’t just make breakfast.

You created calm. You built beauty. You honored tradition.

In France, bakers wake up at 3 a.m. to prepare croissants. They don’t do it for fame. They do it because it’s sacred.

You don’t need to wake up at 3 a.m.

But you can choose to slow down. To care. To make something with your hands that lasts longer than a TikTok scroll.

That’s the quiet revolution of homemade pastry.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about presence.

And maybe—just maybe—that’s why the best croissants taste so good.

They’re made with heart.

Final Thoughts: Taste the Difference, Make It Yours

Let’s recap:

- Laminated dough is the umbrella term for any dough layered with butter through folding.

- Butter croissants are a specific, enriched type of laminated dough—with yeast, milk, sugar, and high-quality butter.

- The magic lies in layering, temperature, and patience—not magic tricks.

- Store-bought “croissants” often skip the real butter and the real process.

- Making them at home isn’t just possible—it’s deeply rewarding.

- And beyond the flakiness? There’s a quiet joy in slowing down, doing something beautiful with your hands, and sharing it with others.

So here’s my challenge to you:

Next weekend, make one croissant. Just one.

Use real butter. Take your time. Don’t rush the chill. Trust the process.

And when you bite into it—warm, flaky, rich, imperfectly perfect—remember:

You didn’t just eat a pastry.

You tasted craftsmanship. You honored tradition. You chose presence over speed.

That’s worth more than any Instagram post.

If you try it, I’d love to hear how it went. Did your layers separate? Did your kitchen smell like heaven? Did you accidentally make too many and eat three for breakfast?

Drop a comment below. Share your story.

And if you found this helpful? Pass it on. Send it to a friend who loves food, or to someone who needs a reason to slow down.

Because sometimes, the most powerful thing we can bake isn’t a croissant.

It’s connection.

Happy baking.

Thayná Alves is an influential digital content creator who has carved out a significant space in the realms of technology, finance, and entrepreneurship. Through her blog, Newbacker.com , she stands out as an authentic and accessible voice for individuals seeking practical information about investments, innovation, and emerging trends in the financial market.