There’s nothing quite as disappointing as pulling a loaf of bread out of the oven only to find it heavy, gummy, or brick-like—especially after hours of effort and anticipation. You followed the recipe, measured the ingredients, and waited patiently for it to rise… so what went wrong? Don’t worry—you’re not alone. Even experienced bakers occasionally wrestle with dense bread. The good news? Most of the time, the problem has a straightforward cause and an even simpler fix.

In this article, we’ll explore the most common reasons your bread turns out dense, from yeast issues and improper kneading to oven missteps and humidity challenges. More importantly, we’ll give you practical, kitchen-tested solutions so your next loaf comes out light, airy, and full of flavor. Whether you’re a weekend baker or dreaming of artisan loaves, understanding these fundamentals can transform your results—and your confidence in the kitchen.

Let’s dive into the science and soul of great breadmaking, one fluffy slice at a time.

1. Yeast: The Tiny Powerhouse Behind Fluffy Bread

Yeast might be microscopic, but its impact on your loaf is enormous. This living organism feeds on sugars in your dough and produces carbon dioxide gas, which gets trapped in the gluten network—creating those beautiful air pockets that give bread its light texture. If your bread is dense, the first place to look is your yeast.

Is your yeast still alive? Yeast has a shelf life. Even if it’s within the expiration date, improper storage (like exposure to heat or humidity) can kill it. To test if your yeast is active, dissolve it in warm water (105–110°F or 40–43°C) with a pinch of sugar. Within 5–10 minutes, it should foam and bubble. If it doesn’t, it’s dead—and your dough won’t rise.

Water temperature matters more than you think. Too hot (above 130°F/54°C), and you’ll kill the yeast. Too cold, and it won’t activate properly. A kitchen thermometer can be a game-changer here.

Also, consider the type of yeast you’re using. Instant yeast can be mixed directly with flour, while active dry yeast needs proofing. Substituting one for the other without adjusting technique can lead to under-risen dough.

Pro Tip: If you bake infrequently, store yeast in the freezer. It stays viable much longer than at room temperature.

When yeast is healthy and treated right, it transforms flour and water into something magical. Neglect it, and you’ll end up with a doorstop instead of dinner.

2. Kneading and Gluten Development: Building the Right Structure

Even with perfect yeast, your bread can still turn out dense if the gluten network isn’t developed properly. Gluten—the elastic protein formed when flour meets water—is what traps the gas produced by yeast, allowing your dough to rise and hold its shape.

Under-kneading is a frequent culprit. Without enough kneading, gluten strands remain weak and fragmented, unable to hold air bubbles. The result? A compact, chewy loaf with little volume.

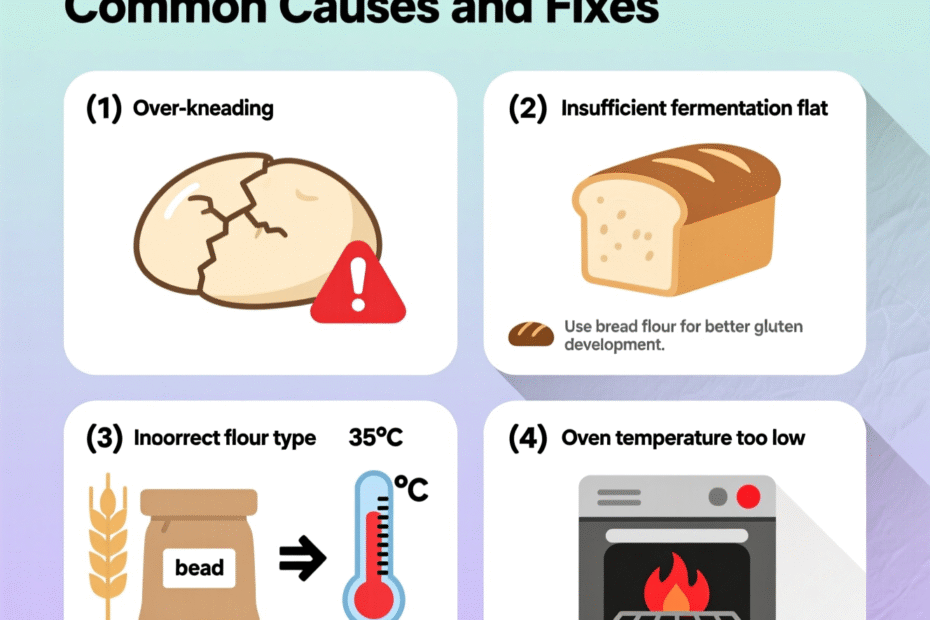

Over-kneading, especially with a stand mixer, can also backfire. Too much mechanical action breaks down gluten, leading to a collapsed or gummy crumb. Dough should feel smooth, elastic, and slightly tacky—but not sticky—when properly kneaded.

How do you know when you’ve kneaded enough? Try the windowpane test: take a small piece of dough and gently stretch it between your fingers. If it forms a thin, translucent membrane without tearing, your gluten is ready. If it rips immediately, keep kneading.

For no-knead bread enthusiasts, time replaces manual effort. These recipes rely on long fermentation (12–24 hours) to develop gluten naturally. But even then, a gentle fold or two during bulk fermentation can strengthen structure.

Remember: Different flours behave differently. Bread flour has more protein (12–14%) than all-purpose (10–12%), which means better gluten formation. If you’re using whole wheat or rye, consider blending with bread flour for improved rise.

A well-developed gluten structure is like a balloon—strong enough to expand, but supple enough to stretch. Get this right, and you’re halfway to perfect bread.

3. Proofing: The Art of Patience (and Timing)

Proofing—the period when dough rises—is where flavor and texture truly develop. But many bakers unintentionally sabotage their loaves by rushing or overextending this stage.

Under-proofing means the yeast hasn’t produced enough gas to create air pockets. The dough may look small and tight, and when baked, it expands slightly in the oven (known as “oven spring”) but quickly collapses into density.

Over-proofing is just as problematic. When dough rises too long, the yeast exhausts its food supply and the gluten structure weakens. The dough becomes fragile, collapses during baking, and yields a flat, gummy loaf with large, uneven holes or none at all.

How can you tell when dough is perfectly proofed? Use the poke test: gently press a floured finger about ½ inch into the dough.

- If the indentation springs back quickly → under-proofed.

- If it springs back slowly and leaves a slight dent → ready to bake.

- If it doesn’t spring back at all → over-proofed.

Environmental factors matter too. Cold kitchens slow fermentation; warm ones speed it up. In winter, try proofing your dough in a slightly warmed oven (with the light on) or near a radiator. In summer, keep an eye on it—it can over-proof in half the expected time.

Also, don’t skip the second rise (after shaping). This final proof ensures your loaf has enough lift to create an open crumb. Skipping it often leads to tight, dense bread—even if the first rise looked great.

Proofing isn’t just waiting—it’s active observation. Treat it with care, and your bread will reward you with loft and lightness.

4. Baking Techniques and Oven Environment

Even if your dough is perfectly mixed, kneaded, and proofed, a misstep in the oven can still lead to dense bread. Baking is where chemistry meets physics—and small details make a big difference.

Oven temperature is critical. If your oven runs cool (which many do), your bread won’t get enough oven spring—the final burst of rising that happens in the first 10 minutes of baking. Use an oven thermometer to verify actual temperature; you might be surprised by the discrepancy.

Steam creates lift. Professional bakers inject steam into ovens to keep the crust soft during early baking, allowing the loaf to expand fully. At home, you can mimic this by placing a pan of boiling water on the bottom rack or spritzing the dough with water before closing the oven door. Another hack: bake inside a preheated Dutch oven—the trapped moisture acts like a mini steam chamber.

Don’t open the oven too soon. Peeking during the first 15–20 minutes releases heat and steam, halting oven spring and potentially causing collapse. Resist the urge—your patience will pay off.

Also, bake long enough. Underbaked bread feels soft but quickly firms up into a gummy, dense mass as it cools. Use a digital thermometer: most bread is done at an internal temperature of 190–210°F (88–99°C), depending on the type (lean breads like baguettes aim for 205–210°F; enriched breads like brioche around 190°F).

Finally, cool completely before slicing. Cutting into hot bread releases trapped steam, making the crumb wet and dense. Wait at least 30–60 minutes—it’s torture, but essential.

Your oven isn’t just a heat box—it’s a transformation chamber. Treat it with respect, and your bread will rise to the occasion.

5. Foour, Hydration, and Hidden Variables

Sometimes, the problem isn’t technique—it’s ingredients or environment. Seemingly minor choices can have major consequences.

Flour quality and type play a huge role. Whole grain flours (like whole wheat, spelt, or rye) contain bran and germ that cut through gluten strands, limiting rise. If you love whole grains, try using 75% bread flour and 25% whole wheat as a starting point, then adjust based on results.

Hydration level—the ratio of water to flour—also affects density. Too little water, and your dough is stiff, inhibiting gluten development and yeast activity. Too much, and the dough becomes slack and hard to handle, potentially collapsing. Most beginner-friendly doughs are around 60–65% hydration (e.g., 600g water per 1000g flour). Advanced bakers work with 75–80% for open crumb, but that requires skill.

Altitude and humidity are silent influencers. At high altitudes, dough rises faster due to lower air pressure, increasing the risk of over-proofing. In dry climates, flour absorbs more moisture, so you may need to add extra water. In humid areas, the opposite is true.

And don’t forget salt! While it strengthens gluten and controls yeast, too much can inhibit fermentation. Stick to 1.8–2% of flour weight (e.g., 18–20g salt per 1000g flour).

Baking is part science, part intuition. Pay attention to your ingredients and surroundings—they’re part of the conversation.

Conclusion: Bake with Confidence, Not Fear

Dense bread isn’t a failure—it’s feedback. Every collapsed loaf, every gummy crumb, teaches you something about yeast, gluten, timing, or your own kitchen environment. By understanding the common causes—inactive yeast, poor gluten development, improper proofing, baking missteps, and ingredient variables—you gain the power to troubleshoot and improve.

Remember: great bread doesn’t require perfection. It requires curiosity, patience, and a willingness to learn from each bake. Even master bakers have off days. What matters is returning to the counter, flour-dusted and determined, to try again.

So next time your loaf feels a little heavy, don’t toss it—use it as a lesson. Adjust one variable. Keep notes. Celebrate small wins. Before you know it, you’ll be pulling golden, airy loaves from your oven that rival your favorite bakery’s.

Now it’s your turn: What’s the #1 bread-baking challenge you’ve faced? Share your story in the comments below—let’s troubleshoot together! And if this guide helped you, don’t forget to share it with a fellow baker. Happy baking!

Thayná Alves is an influential digital content creator who has carved out a significant space in the realms of technology, finance, and entrepreneurship. Through her blog, Newbacker.com , she stands out as an authentic and accessible voice for individuals seeking practical information about investments, innovation, and emerging trends in the financial market.